Listen to the article

A review of The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom by David Woodman, 344 pages, Princeton University Press (September 2025).

Romanophiles know that the first Roman emperor was Augustus. Serious Muslims know that the first caliph after Muhammad was Abu Bakr. Likewise, Americans know their first President was George Washington. Ask an Englishman who the first king of England was, however, and the answer is likely to be rather hazy.

The prevailing paradigm is that English history didn’t really begin until after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, when William the Conqueror ascended to the throne. Pre-Conquest England is murky, barbarous Dark Ages stuff. Take a BBC4 documentary last year on the Bayeux Tapestry, in which the British historians thought it hilarious to contrast what they saw as the unsophisticated, drunken, gluttonous feasting in the tapestry’s Anglo-Saxon scenes with the refined, civilised, convivial banqueting of the Normans.

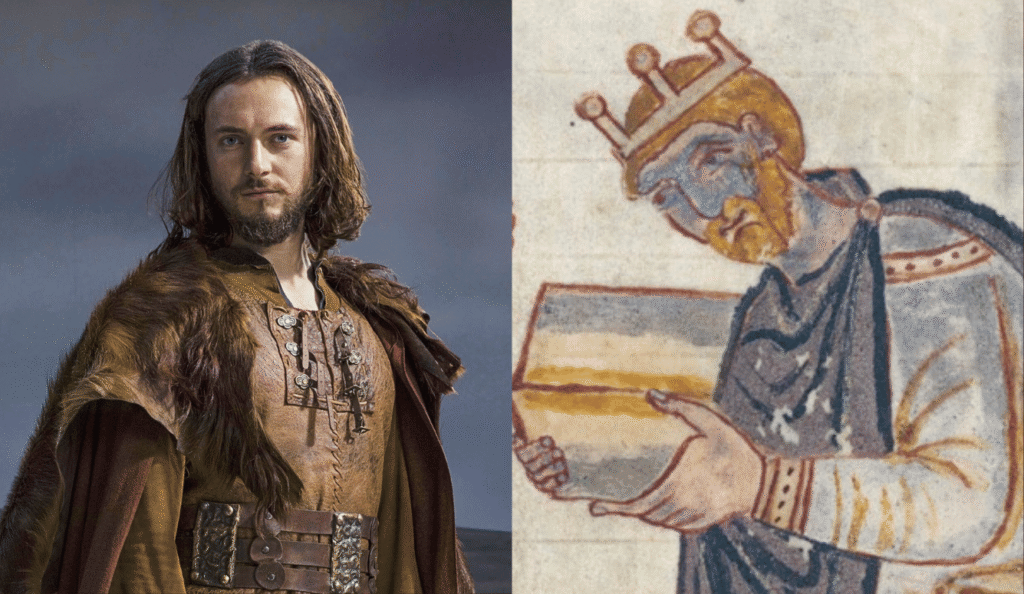

All English monarchs since, including the current one, have claimed William I as their distant kinsman. But William was simply the first Norman king of England, not the first king, full stop. It was Athelstan of House Wessex, who as David Woodman argues in his new biography, was “the first person who could legitimately be titled ‘King of the English’” (though technically not “King of England,” a title first used by the Danish king Cnut in 1016). But for someone who was so influential in English history, his life story is unusually obscure. The doyen of Anglo-Saxon studies Frank Stenton once described Athelstan as the “greatest English statesman for whom no biography exists.”

At last, he has been getting his due. In 2021, The Rest Is History podcast staged a ‘world cup’ to decide on the greatest monarch in English history. Athelstan beat the likes of Queen Victoria and Elizabeth I to come out on top. That the listeners chose the first Rex Angelsaxonum was so surprising that it was reported in the press.

Woodman is not the first person to write a biography of Athelstan. Sarah Foot’s enlightening 2011 book has the distinction of being the first full written account of Athelstan. The Rest Is History co-host Tom Holland provided a compact biography for the 2016 Penguin monarch series. All three of these histories (including Woodman’s) are attempts to rescue Athelstan from obscurity and give him the prestige he deserves. Woodman’s and Foot’s accounts are educative yet dry in the way academic histories tend to be. Woodman’s intended audience is by no means the casual history buff, so the book contains plenty of in-depth scholarly research alongside interesting information about a rather enigmatic figure.

Many things can be said for Athelstan. He was a formidable conqueror who never lost a battle, fighting alongside his men, rather than leading from the rear. Not only was he the first king of the English, but he also secured overlordship over the Scots and Welsh, making him the most powerful ruler in the British Isles since the Roman emperors. Like Charlemagne, he successfully consolidated multiple kingdoms into one unified realm. He was known to historians and chroniclers as a profoundly pious king who founded churches and monasteries, including Malmesbury Abbey where he was entombed. He was an avid collector of holy relics and a champion of ecclesiastical learning. He also seems to have been an exemplar of medieval Christian kingship, ruling by law as much as by the sword. Woodman describes him as an “extraordinary individual” and one of England’s “greatest” kings.

In the 870s, under Athelstan’s grandfather, Alfred the Great, parts of northern and eastern England were so heavily populated by Viking settlers that they had taken on a distinctively Scandinavian character. The region was later called the “Danelaw.” According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in January 878, Alfred was on the “brink of defeat” when “after twelfth night, the Danish army stole out to Chippenham.” The rapid invasion caught the West Saxons off guard, allowing the Danes to overrun much of Wessex, the last remaining independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Alfred himself went into hiding.

At this point, Alfred was basically a king without a throne—but he was not beaten. For months, he waged guerilla warfare from his fortress in Athelney and secretly rallied loyalists in the surrounding shires against the “Great Heathen Army.” In the end he recovered from his setbacks and, at the battle of Edington, forced the Vikings to surrender. In the peace treaty that followed, only the Vikings had to give up prisoners—there was no mutual prisoner exchange as had occurred after previous battles, which shows the extent of Alfred’s victory.

In the 880s, in the face of Viking aggression, Woodman writes, the idea that Alfred wasn’t just King of Wessex, but King of the Anglo-Saxons began to grow and with it the idea of being “English”—or “Angelcynn” in Old English. After Alfred’s death in 899 AD, his son Edward the Elder ascended to the throne and further consolidated and built upon his father’s gains, conquering lands from the Vikings in the East Midlands and East Anglia, annexing Mercia, and expanding the burghal system, a network of fortified settlements formed under Alfred’s reign to defend against Viking raids and centralise royal authority, which laid a sturdy foundation for Athelstan’s kingdom (many English medieval boroughs and towns evolved out of these burghs).

Woodman is candid about the fact that no biography of Athelstan can provide a clear chronological list of events, as there are “too many holes to be plugged.” A lot of Athelstan’s early life is opaque, though some of his rivals claimed that his mother, Ecgwynn, was of low birth, making him unfit to claim the throne. After his father’s second marriage, Athelstan’s position weakened. In 901 AD, two royal decrees demoted him in the line of the succession behind his uncle and his nephew. Nevertheless, after Edward the Elder’s death in 924 AD, Athelstan assumed the throne with little challenge and Aelfweard, his elder brother, died sixteen days later. After his coronation, Athelstan styled himself Angulsaxonum Rex (King of the Anglo-Saxons) thus “declaring himself to be the successor to the kingdom created by his grandfather and perpetuated and extended territorially by his father.”

The conquest and assimilation of Northumbria into Athelstan’s new kingdom in 937 AD was, Woodman writes, “one of the most significant events in English history.” It was when “an England of a recognisable geographical and political form was born.” The Battle of Brunanburgh, where Athelstan’s English army fought off the Norse–Scots alliance is the battle that made England. Yet its location remains a mystery, hotly debated by historians, to this day. Thousands are said to have been slaughtered, including five young kings and seven Norse Jarls.

The battle was so bloody that the Anglo-Saxon chroniclers resorted to poetry to capture its gravity and preserve its glory for a millennium. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a dry document; it is not like reading Herodotus or Sima Qian. Most of the entries are recorded in arid, factual prose that rarely exceeds a few sentences, without any emotion or ornamentation. But the entry for Brunanburgh is a heroic poem in earthy Old English, which opens with a thunderous veneration of Athelstan and his brother, Edmund, for defeating the Norsemen and their allies on a battlefield that “flowed / with dark blood.” Later on, there is a solemn acknowledgement of the sacrifice that it took to establish the united English kingdom:

Read the full article here

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using AI-powered analysis and real-time sources.