Listen to the article

Since returning to the White House more than one year ago, President Trump and his administration have continued to take steps on multiple fronts to impinge on the independence of the press.

For example, the Trump administration has taken over the White House press pool, defunded public media, investigated news outlets, rolled back Justice Department protections for journalists, forced reporters who cover the military out of the Pentagon, and, most recently, raided the home of a Washington Post reporter and seized her electronic devices.

And it’s only been 12 months.

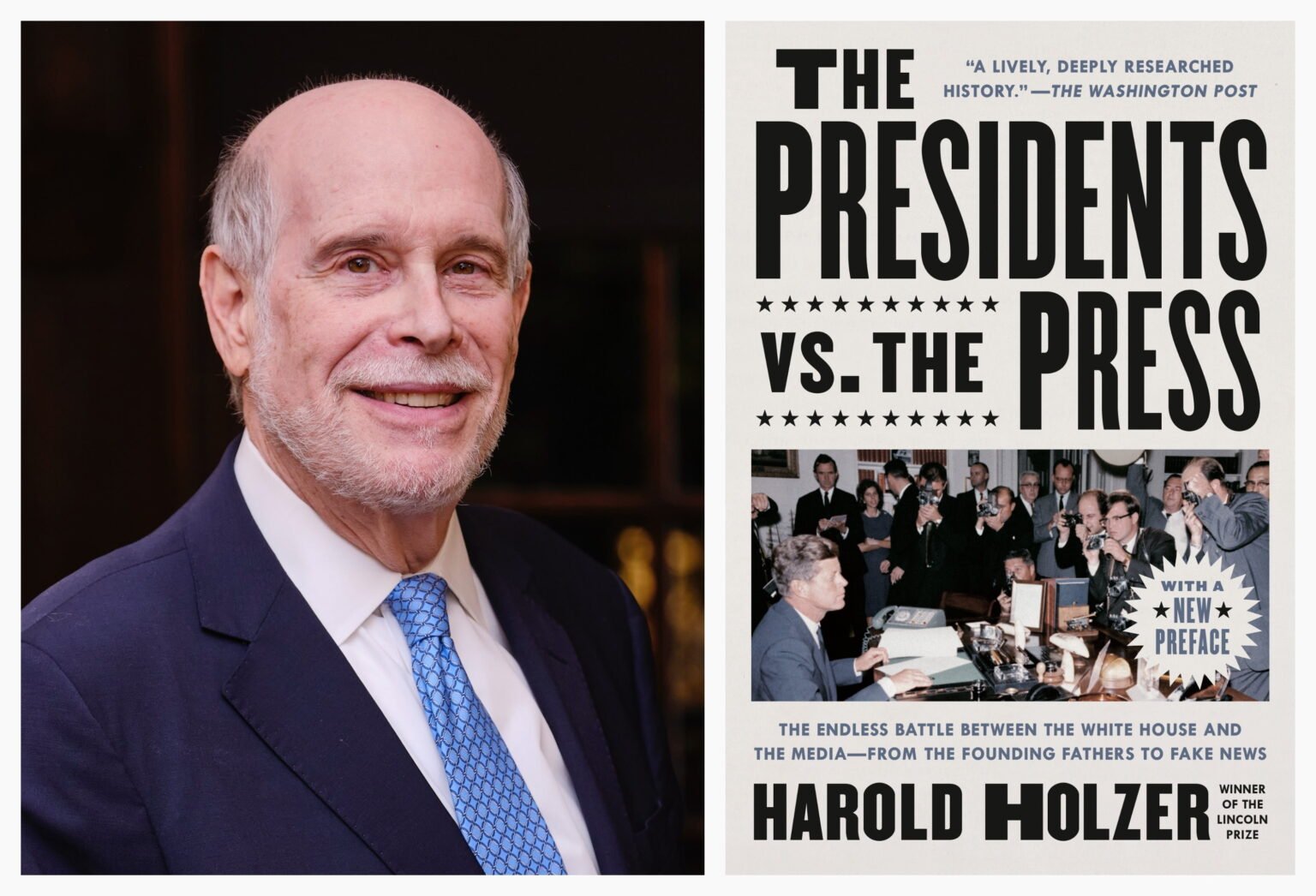

As we prepare for the press freedom battles to come in year two, we thought it would be a good time to get some historical perspective on Trump’s relationship with the press. And who better to talk to than the man who literally wrote the book on the subject: historian Harold Holzer, author of “The Presidents vs. the Press: The Endless Battle between the White House and the Media — from the Founding Fathers to Fake News.”

Holzer is currently the Jonathan F. Fanton Director of The Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College in New York City. He recently spoke to us via Zoom from his office two floors above where the historian says FDR delivered what was essentially his first “fireside chat” (more on that below). In our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, Holzer discusses Trump’s ongoing fight with the news media, Abraham Lincoln’s wartime censorship campaign, Teddy Roosevelt’s “enemies list,” and why every president hates the press.

How do you view the Trump administration’s actions against the press during this second term?

I think the shock and awe of [Trump’s] first administration is more shocking than the even more outrageous things that they’re doing and the more organized things they’re doing in the second. You know, stripping Jim Acosta of his credentials, revving up crowds at rallies to shout down CNN journalists or other journalists and actually making them fear for their lives. I just think that the shock value of all that was unequaled. [In Trump’s second term,] his actions are much more insidious, much more dangerous.

Is the FBI search of a Washington Post reporter’s home a significant escalation in Trump’s crackdown against the press?

An escalation, but not really a surprise. Whether by lawsuit or intimidation, the administration has been eroding press freedom and independence, and by acquiescence, some in the media have encouraged their own surrender. Until the pushback gets louder, and the courts get more involved, I expect the situation to get worse before it gets better.

What was your reaction to the Trump administration’s decision to take over the White House press pool? That has never happened before, right?

Right. Why don’t [reporters] all walk out like they did at the Pentagon? See how [Trump] likes it for a week. I’m old school. I think that the press corps should be in charge of the press corps. The pooling should be arranged by the press corps. There’s no reason in an alleged democracy to change that tradition.

A lot of people today might assume that Trump is the most anti-press president in our nation’s history. But is that true?

The thing that makes it a little bit apples and oranges is that in the 19th century, 85 percent of the newspapers were affiliated with political parties. Editors were politicians. Politicians were editors. It was just part of the culture that the crossover existed.

And in that culture, no one cracked down on journalism more than Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s administration had a lot of agencies involved in censoring the press: the State Department, the Post Office Department, the Interior Department, and the biggest army in the history of the world.

As I pointed out in my book, [Lincoln] never said, “I am suspending every Democratic newspaper that argues against the war.” It was always case by case, and it was informal and a little disorganized. What he was worried about mostly were democratic cities like New York, because he had lost so badly in New York City, and he was worried about another eruption of violence like the draft riots. And he was worried about the border states: Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. He threw a lot of editors into jail.

Francis Scott Key’s grandson, who published anti-union sentiments, ended up imprisoned in Fort McHenry, which was the same fort where the guy’s grandfather had seen bombs bursting in air, inspiring him to write the “Star Spangled Banner.” How’s that for the irony of 50 years of change from 1812 to 1861?

Are presidents’ relationships with the press usually tense during wartime?

In wartime, it always gets dicey. Wilson and Kennedy, in his informal wars, and Johnson in Vietnam and FDR in World War II, not only cracked down on the press, but created their own propaganda mechanisms, particularly Wilson and Roosevelt in World War I and II.

The Committee for Public Information — the Creel Committee — under Wilson put out alternate stories. FDR had film units headed by the great movie directors like John Ford and Frank Capra and George Stevens, who went out and made propaganda films and they took hold, and that kind of enabled them to be friendlier to the press.

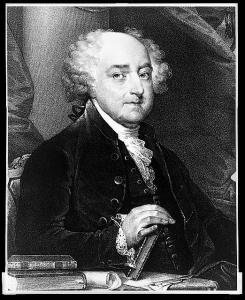

What about John Adams’s war against the press?

Adams legislated a crackdown on opposition papers. Something as amorphous as making fun of the president became a crime. The Alien and Sedition Act is clearly, legislatively, the most oppressive anti-freedom-of-the-press thing ever published. But who was going to object? Every federal judge in the United States had been appointed by either George Washington or John Adams, so they’re all Federalists, and no one was going to object to any of that stuff until Jefferson gets to appoint some judges, and the bill sunsets.

And we shouldn’t only blame Adams. When I wrote “The Presidents vs. the Press,” I was kind of shocked to find communications from George Washington saying: “Go, Adams! I would have done more.”

Your book makes it very clear that pretty much every president, to varying degrees, hated the press. Why do you think that is? Did they just think they would be able to manipulate them or win them over?

Yes! And they don’t like criticism. Have you ever met a president? I’ve met a lot of them, more than my fair share. I think I know Clinton the best. Clinton thought he got a raw deal because he did things in the beginning to irritate [journalists], like block the door to the press room. Why would you do that?

I knew George W. Bush fairly well, and [George H.W.] Bush. They all disliked the press. Carter hated the press. I only met him once or twice, but he hated [the press] because they made fun of him. Nixon was maniacal about the press. I didn’t meet Nixon, but I knew a lot of people who were on his “enemies list.”

“Theodore Roosevelt believed that if you criticized the president

you were put on his enemies list. You were ostracized,

and then you couldn’t come in for the barber’s hour to watch him being shaved.”— Harold Holzer

Theodore Roosevelt believed that if you criticized the president you were put on his enemies list: the “Ananias Club,” as he called it. You were ostracized, and then you couldn’t come in for the barber’s hour to watch him being shaved. And then the press gets back at him. They love asking him the most disobliging questions when the barber’s got the razor on his neck because they know he’ll jump up and they want to see if they could draw blood.

Didn’t Teddy Roosevelt have a good relationship with “Muckrakers” like Ida Tarbell?

He liked Ida Tarbell, but in the end, he distanced himself from the Muckrakers. He attacked the muckrakers. People don’t realize that he used them. He certainly depended on them to raise big issues that he could legislate around, move public opinion on. And then he decided their name was well-founded because they love digging in the mud and getting dirty, and we have much more pleasant things to talk about. But that’s what he did. Yeah, they all turn on the press, including Teddy.

Going back to Trump again, which previous president does he most closely resemble in his interactions with the press?

The closest [comparison] is Adams, because he’s totally resistant to criticism. With Adams, the idea that you couldn’t make fun of the president has that same kind of megalomania and insecurity that we sometimes attach to President Trump. Adams was both egotistical and insecure. He felt that he was the neglected founding father, and therefore he had to build himself up and could tolerate the least criticism.

Which presidents stand out to you most for how they used technologies to either evade or manipulate the news media?

Well, Lincoln, because by the end of the Civil War, he was his own war correspondent. He was filing dispatches on the telegraph wires from the seat of war in Petersburg and Richmond. He was a terrific communicator, and he wrote in a way that was understandable, comprehensible, not ornate and flowery.

Wilson, because he felt confident enough to have the first presidential press conference, even though the questions had to be submitted in advance.

FDR. On the day after the election of 1932, Hoover had not conceded. So Roosevelt was wheeled into the family parlor on the second floor of this house and spoke in front of the fireplace. So essentially it was his first fireside chat. This is a guy who understood radio, and it was the dawn of network radio and also film. He was the absolute master of the technology of mass communication, and he had such a beautiful voice.

Obama, I guess, with the White House website was important. But look, give Trump his due. He is one of the most ingenious communicators ever, from the days when he would call up journalists in a disguised voice and say that he’s the greatest lover in New York to the tweeting. Nobody’s been as good, as fast, as reckless, as impactful, certainly not in the last 20 years.

I know you were a journalist early in your career. If you could travel back in time and work as a reporter covering any one of these administrations, which president would you want to cover?

Lincoln or [Franklin] Roosevelt because I love them the most. Roosevelt had picnics for reporters at Hyde Park and baseball games and swimming and tennis. It would have been great just to bask in these extraordinary people. And then I would get to talk to Eleanor. I would love to have met her.

But [covering] Lincoln would be extraordinary. He’s still mysterious enough for the reporter in me to want to ask him some questions about immigration and emancipation and his father and his wife and other things that you can’t find out about anymore.

Read the full article here

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using AI-powered analysis and real-time sources.