Listen to the article

For decades, Costa Rica was held up as Central America’s democratic exception: a country without an army, with strong democratic institutions, and a press able to scrutinize those in power without facing systematic retaliation.

That reputation is now being tested as Costa Rica heads into presidential elections that will culminate in a first round on February 1 and could extend to a runoff in April. The race is widely seen as a test of whether the country will correct course and reaffirm its democratic identity or deepen recent trends of populist governance and institutional weakening.

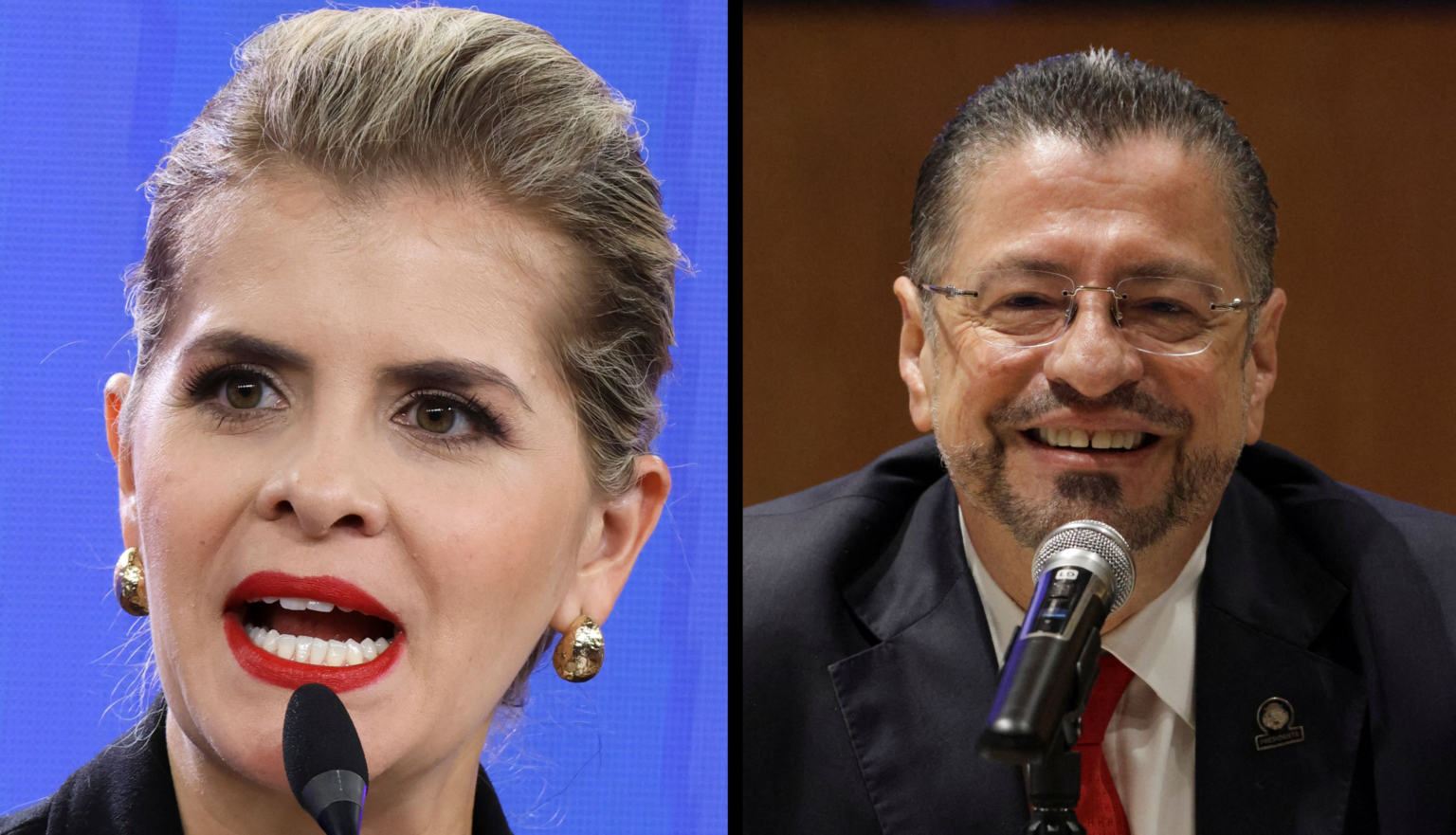

Populist President Rodrigo Chaves of the Sovereign People Party is constitutionally barred from immediate re-election. However, his party’s candidate Laura Fernández and allied political forces are seeking to retain the executive power and increase their legislative representation as opposition candidates have pledged to restore access to information and ease tensions with the press. According to the latest poll, Fernández is projected to win in the first round.

From the outset of his presidency, Chaves has made confrontation with the press a central feature [apparatus] of his political strategy. Public attacks against journalists, repeated denunciations of critical media outlets, restrictions on access to public information, the use of state institutions to pressure companies linked to media organizations, and the discretionary use of state advertising have marked a governing style that press freedom advocates say has steadily narrowed the space for independent journalism.

The stakes extend well beyond Costa Rica. For years, the country’s relative institutional strength made it a key refuge for journalists forced into exile from across Central America, where independent media have been criminalized, shuttered, or pushed underground. That sense of safety has begun to erode. Rising insecurity has made Costa Rica less uniformly safe, particularly for exiled reporters from Nicaragua who remain publicly visible or continue investigating powerful actors, adding new risks to an already fragile situation.

Press freedom advocates warn that the convergence of growing insecurity, sustained political hostility toward the press, and weakening institutional protections is narrowing the space for journalism in Costa Rica itself, while also undermining its role as a regional haven. These pressures are unfolding amid a broader context of democratic erosion and shrinking international support, as cuts to democracy and civil society funding has left journalists, independent media, and oversight bodies more exposed to political and economic pressure.

CPJ spoke with Yanancy Noguera, president of the Costa Rican Journalists’ Association (Colegio de Periodistas de Costa Rica), about how these dynamics have unfolded over the past four years, how they are shaping election coverage, and what their long-term implications could be for press freedom and democratic accountability.

The Costa Rican presidency failed to respond to CPJ’s emailed request for comment on press freedom restrictions.

The interview was conducted in Spanish and has been edited for clarity and length.

Costa Rica has historically been considered a democratic benchmark. Over the past four years, what concrete changes have you observed in the environment for press freedom?

Most of the changes have to do with the way the press and related organizations have had to confront mechanisms that are illegal, irregular, immoral, unethical, and improper, applied by the Chaves administration against independent media.

This is tied, first and foremost, to a president who was heavily scrutinized by the press during his campaign. Coming from an international organization and running for the presidency, he had faced a sexual harassment case that the World Bank resolved by restricting his access to certain facilities. When this was reported, he denied it without providing evidence and claimed it was part of media attacks against him.

During his campaign, he used the term “canalla press” (“scoundrel press”). Once elected, the president implemented a continuous pattern of personal attacks against journalists and media outlets, public discrediting, and obstacles to journalistic work.

He later adopted administrative actions, using state institutions such as the Ministry of Health to shut down organizations linked to media outlets and to pressure media owners. A constant campaign of attacks targeting specific journalists, smear campaigns, and repeated disqualifications emerged, producing a logic of censorship and self-censorship.

In this electoral period, what are the most relevant threats to journalism, and how are they manifesting?

There are currently 20 parties competing in the presidential race. Of these, only two do not maintain a respectful discourse toward the press. The other 18 may dispute specific publications but remain within the normal boundaries of press–power relations.

The ruling party maintains the same aggressive discourse it has sustained throughout the administration, combined with the denial of information. The other party is an evangelical political group allied with the ruling party in the Legislative Assembly, led by Fabricio Alvarado. This alliance has also manifested during the campaign, including offers to evangelical pastors to occupy legislative seats or positions in a potential continuation of the ruling party in power.

You have mentioned stigmatization of the press. How does this recurring pattern operate?

The Wednesday press conferences function as staged events with predefined scripts, following a logic similar to that of other governments in Latin America. Influencers presented as journalists are typically given priority to ask questions aligned with the government’s narrative, often aimed at dismantling reporting by independent media.

The president is usually accompanied by ministers or officials, and prepared dialogues are used to discredit specific journalists and outlets. Publications are labeled false, independence is questioned, and journalists are attacked publicly, whether present or not.

A particularly clear example occurred at the start of the electoral period, when the ban on government advertising came into force because of the elections. That same day, all executive institutions published a graphic stating, “the gag has fallen.” Despite legal warnings, the executive ignored the restrictions and treated the sanctions as a minor cost.

Costa Rica has a strong institutional structure. How effective has the institutional response been?

The Constitutional Chamber has been fundamental with the rulings (including rulings related to restrictions on state advertising and cases involving the closure of one source of income of a media outlet). However, Costa Rican democracy was not prepared to confront this level of irresponsibility from the executive branch.

The system of checks and balances assumes that rulings from the judiciary, the Legislative Assembly, or any other institution will eventually be respected. In this case, rulings are not only ignored but publicly discredited, facts are denied, and false narratives are constructed to misinform the public.

There is a cynical use of institutions, exploiting the immunity and legal protections of public officials. When there is no minimum level of democratic decency, legality loses effectiveness. The legal system does not respond adequately when those in power mock institutions and use disinformation to delegitimize democratic oversight.

How are post-truth narratives, disinformation, and accusations of ‘fake news’ being used?

The government has developed multiple forms of discrediting, ranging from direct verbal attacks at public events to more elaborate staged efforts.

False narratives have been constructed without factual basis but presented convincingly to audiences predisposed to distrust the press. This use of post-truth is highly harmful to the information ecosystem needed for informed decision-making.

Throughout the electoral process, officials have sustained claims that they are being blocked from governing and that a supermajority in congress is needed to “move the country forward.” This discourse has been accompanied by suggestions that the president could return to power, despite constitutional prohibitions on consecutive re-election.

If these dynamics deepen, what would be the impact on democracy and on the press?

If political continuity is consolidated, the damage could be largely irreversible. This is how democratic erosion begins and further consolidation would likely deepen structural uncertainty.

Deterioration is already visible in education, health, and infrastructure. Violence and insecurity have reached unprecedented levels without effective policies to address them. Distrust will increasingly shape everyday life, social cohesion, and civic participation.

For the press, four more years under these conditions would be exhausting. New independent outlets are unlikely to emerge. Journalists face the absence of state advertising, limited audience willingness to pay for news, and a permanently hostile environment.

In the best case, journalism stagnates. In the worst, outlets close and journalists leave the profession, particularly younger reporters unwilling to endure constant harassment. This weakens accountability while politically aligned content creators with opaque funding gain influence.

Why should the international community care, and how can it help?

Costa Rica has long been viewed as a democratic model. When such a model deteriorates, preventive international scrutiny matters. While global attention often focuses on more extreme cases, democratic erosion in stable systems also deserves attention.

International warnings alone have limited impact when governments lack the will to listen and discredit organizations issuing alerts. Without additional pressure mechanisms, such as linking international financing to democratic standards, these warnings struggle to produce change.

But one thing is true. Solidarity remains essential. Costa Rican journalists need to know they are not alone. Strengthening cooperation among journalists and resisting attempts to divide the press into “good” and “bad” media is critical.

Read the full article here

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using AI-powered analysis and real-time sources.