Listen to the article

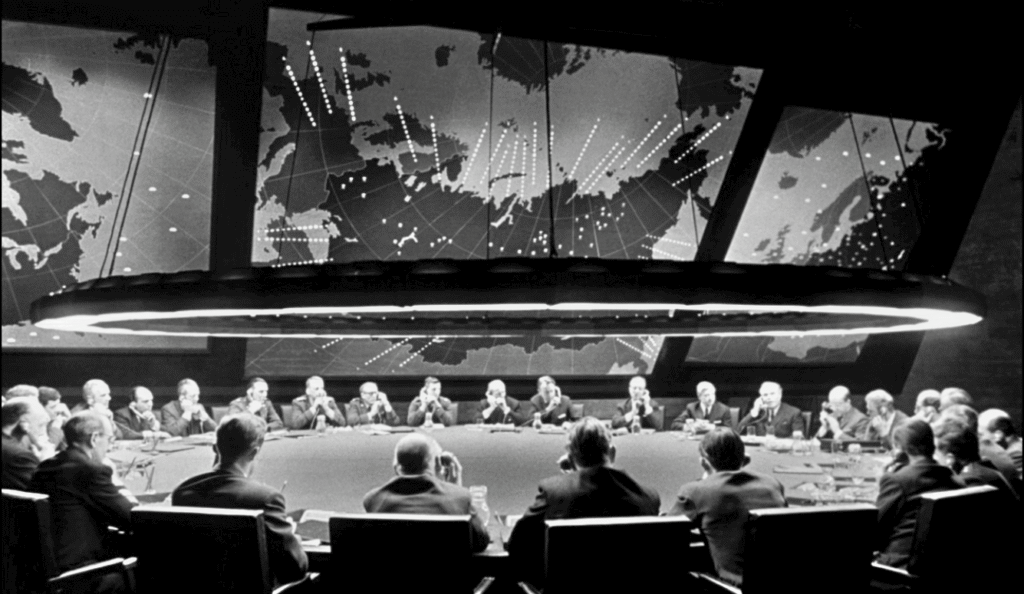

“Do you realise that fluoridation is the most monstrously conceived and dangerous communist plot we’ve ever had to face?” This isn’t RFK Jr talking. It’s General Jack D. Ripper, played by Sterling Hayden in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Ripper believes that the Soviets are poisoning America’s drinking water to make all Americans, including him, sexually impotent, so he goes rogue and orders the nuclear-armed B52 bombers under his command to attack Russia. US President Merkin Muffley (played by Peter Sellers), General Buck Turgidson (played by George C. Scott) and Soviet Ambassador Alexei de Sadesky (played by Peter Bull) race to stop the planes before they reach their targets and prompt nuclear retaliation by the Soviets and an atomic conflagration leading to the two superpowers’ mutual destruction. All this is set off by one man’s wounded ego.

Dr Strangelove wasn’t meant to be a comedy. The film began as an adaption of Peter George’s Cold War thriller Red Alert, but the longer Kubrick spent thinking about and writing the film, the more he found that the Cold War politics of mutually assured destruction (MAD) could only be the stuff of jokes. George Case cites Kubrick in his book Calling Dr Strangelove: The Anatomy and Influence of the Kubrick Masterpiece:

What could be more absurd than the very idea of two mega-powers willing to wipe out all human life because of an accident, spiced up by political differences that will seem as meaningless to people a hundred years from now as the theological conflicts of the Middle Ages appear to us today?

Some of the film’s most iconic moments are its lampoons of Cold War politics, such as the Americans’ and Russians’ obsessions with the “gaps” between them and the “races” they are competing in, but Kubrick never shies away from the fact that, beneath the absurdity, the situation is a matter of life or death. He initially intended to end the film with the cast throwing pies at each other but instead chose a montage of nuclear explosions decimating the planet.

According to Case, Kubrick once said that the satirist has a brief shelf life because the world quickly overtakes him. His satire in Dr Strangelove is aimed straight at the Cold War’s political conditions. It could have become dated after the Berlin Wall fell, but it hasn’t. Dr Strangelove’s black comedy has survived the specific political conditions in which it was made. If anything, it is just as applicable to modern politics as George Orwell’s work is, especially after one year of Donald Trump’s second presidency. Both The New Yorker and Quillette’s own Jonathan Kay have drawn comparisons between President Trump, his cabinet, and supporters and the political and military leaders in Dr Strangelove, for whom political and military policy is subordinate to their need to always be the biggest man in the room. Kubrick’s characters may talk of “nuclear combat toe-to-toe with the Russkies,” but modern audiences can watch the film’s apocalyptic inciting incident being handled (or rather mishandled) by its ludicrously inept and egotistical leaders, laugh themselves to tears, and think how little has changed. It seems the fate of the world is still in the hands of fools for whom leadership is an opportunity for self-aggrandisement rather than responsibility.

This is not a case of reducing Dr Strangelove to a mirror for our contemporary politics but of showing how its satire can transcend the specific historical context in which it was made, as 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 have. People are still able to identify with it today because, sadly, we’ve come to expect little if any competence from modern political leaders. “I don’t think it’s quite fair to condemn the whole program because of a single slip-up, Sir,” General Turgidson tells the President when he questions how the safeguards Turgidson put in place have failed to stop Ripper from launching a nuclear strike without presidential authority. He calls the end of the world a “slip-up”! This is reminiscent of the attempts of our own politicians to minimise tragedies that don’t suit their agendas. In similar fashion, Donald Trump has downplayed Russian strikes on Ukraine and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has spent the last two years trying to avoid acknowledging the serious, escalating threat of antisemitism in Australia.

When the film begins, General Ripper appears completely sane. He’s gruff but no more so than you’d expect from a military man. Hayden delivers his lines with the tough authoritative voice you’d expect a competent general to have. He tells his second in command, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, calmly yet sternly, “It looks like we’re in a shooting war.” Ripper proceeds to carry out what he claims are his orders: send the B52s to attack Russia, seal his base, and confiscate all radios to prevent the enemy from using them to transmit instructions to saboteurs. Before informing Mandrake of the (alleged) state of war, Ripper tells him, “I shouldn’t tell you this, Mandrake, but you’re a good officer and you have a right to know.” Ripper seems to be committing a negligible breach of protocol in the name of soldierly comradery before proceeding to carry out his orders in what sounds like a grave situation without wasting any time or energy.

Read the full article here

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using AI-powered analysis and real-time sources.