Listen to the article

Nouvelle Vague—Richard Linklater’s new movie about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s landmark debut feature À Bout de Souffle (Breathless)—is a sheer delight. I’ve seen Breathless four times over the years, and I devoted much of 2024 to writing a mammoth two-part retrospective of Godard’s relentless career and artistic suicide over the 62 years that elapsed between his 1960 breakthrough and his death (by actual suicide of the assisted kind) in 2022 at the age of 91.

Jean-Luc Godard in Retrospect Part I: Abstraction Hero (1930–65)

A brief five-year period produced nearly all the Godard movies that film aficionados still remember, but even these celebrated works have dated poorly.

Jean-Luc Godard in Retrospect Part II: Fanaticism and Failure (1966–2022)

After half a decade of critical adulation, Godard’s career slumped into doctrinaire Maoism, bitterness, incomprehensibility, and irrelevance. It never recovered.

So for me, Nouvelle Vague was a reunion with familiar names and faces from Godard’s early life: his fellow writers at the highbrow Parisian film journal Cahiers du Cinéma (still in existence) where he got his first break as a critic. Several of those writers, including Godard himself, became the leading lights of the late 1950s/early 1960s new wave movement in French movie-making, from which Linklater’s film takes its name. The aim of this movement was to make an intellectual kind of cinema that also resembled life in its raw immediacy. To that end, its progenitors employed a mix of loose vérité cinematic techniques, postmodern self-referentiality, improvised dialogue, intimate stories, and real locations instead of purpose-built sets (usually in the interests of saving money). Godard carried all of this to near-parodic extremes, and Breathless was to remain his signature movie for all of his very long life.

In making Nouvelle Vague, Linklater selected actors for their startling resemblance to Godard and his confrères as they slapdashed Breathless together—or sceptically witnessed it being slapdashed together—during August and September of 1959. There on the screen is Godard’s best friend and rival, François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard). And there’s Jacques Rivette (Jonas Marmy). And there’s Godard himself, brought to life in a debut performance by 31-year-old Guillaume Marbeck, whose physical resemblance to his character—the needle nose, the omnipresent shades, the lupine profile, the prematurely receding hairline and widow’s peak—makes him the most uncanny of all of Linklater’s casting choices.

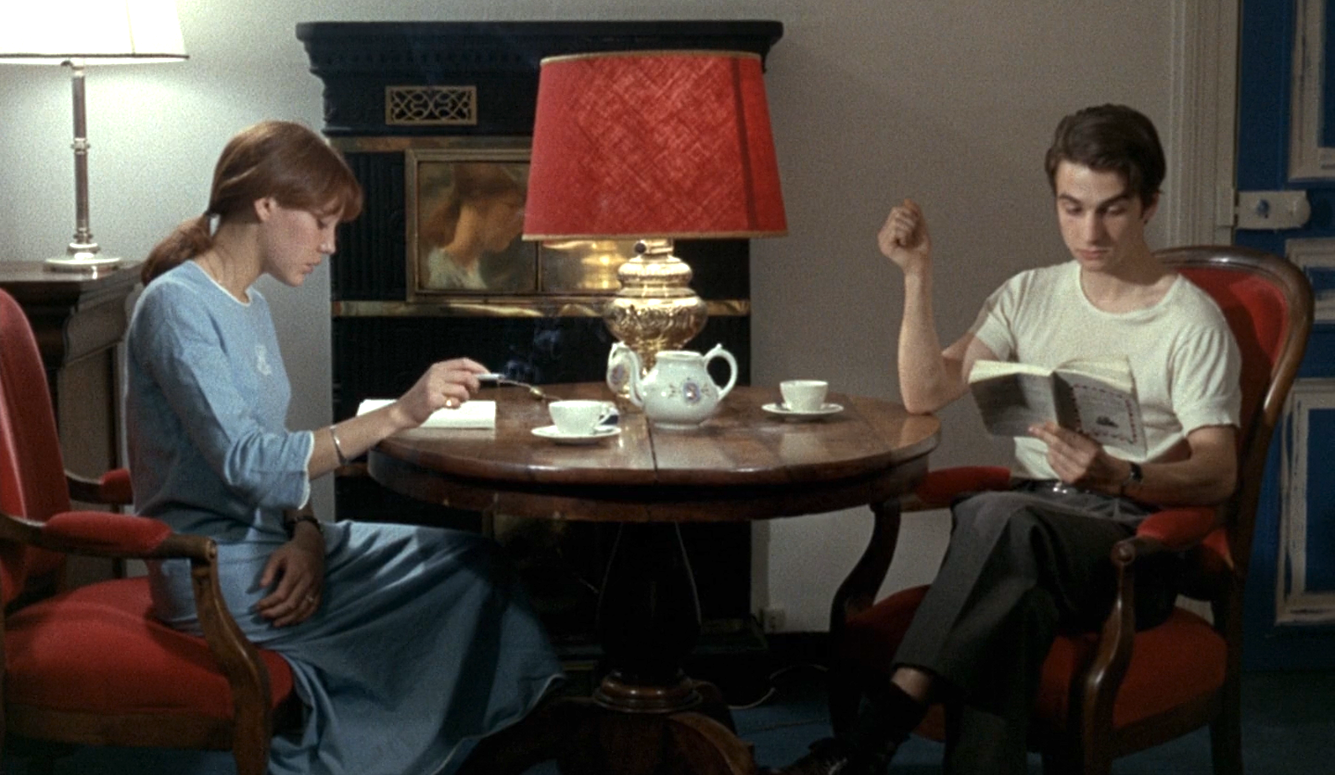

To assist his film’s evocation of the world of sixty years ago, Linklater filmed Nouvelle Vague on grainy monochrome film stock in the 1.37:1 academy aspect ratio that prevailed before the standardisation of the widescreen and cinemascope formats. Nearly all the dialogue is in French with English subtitles (Linklater had the English screenplay translated into French, and he managed to wrangle a crew of mostly French actors despite not being a French speaker himself). As a result, watching Nouvelle Vague in 2025 feels a little like watching an actual Godard film in an American arthouse cinema during the Kennedy administration.

You don’t have to know anything about Breathless—or Cahiers or the French new wave or Godard himself—to be beguiled by Linklater’s film. I watched Nouvelle Vague with a friend who had never seen Breathless and had no idea what was going on for most of the film. Nonetheless, she was enchanted by the late-1950s evening gowns and bouffant skirts worn by Zoey Deutch (who plays Breathless’s twenty-year-old female lead, Jean Seberg), the jazz score, the detailed recreation of mid-century Paris, and the sheer energy and fun of Godard’s seat-of-the-pants directorial style.

Oh, and the cigarettes. The first half of the 20th century was the golden age of smoking. Godard was a lifelong chain-smoker, as was Jean-Paul Belmondo, whom Godard cast as Breathless’s male lead (Aubry Dullin in Linklater’s movie), and so was the small-time hood Belmondo played in Breathless. Seberg also smoked like a chimney both on and off the screen, and in Linklater’s movie she sips wine during an elegant luncheon with a goblet and cigarette in the same hand without setting fire to the tablecloth. Smokes might cause lung cancer in real life, but I found watching mid-century sophisticates elegantly manoeuvring them on film endlessly entertaining.

Nouvelle Vague’s high spirits and heart-on-sleeve affection for its period setting make it a far better movie than Linklater’s simultaneously released Blue Moon, another period piece (set in March 1943) that also purports to dissect show business. Unlike the upbeat Nouvelle Vague, Blue Moon is a real downer: a lugubrious 100-minute near-monologue delivered in real time by the legendary Broadway lyricist Lorenz Hart (“Blue Moon,” “The Lady Is a Tramp”) after he is dumped by his longtime tunesmith collaborator Richard Rodgers in favour of Oscar Hammerstein. For more than an hour and a half, Hart whinges, kvetches, cracks off-colour jokes, derides Oklahoma! as“cornpone,” and half-heartedly courts an arty blonde gold-digger who has come to the bar in the hope of furthering her career as a stage designer. It’s hard to believe that the same Linklater who produced this depressing and mean-spirited portrait also managed to craft the lighthearted valentine to Breathless.

It sounds like heresy to say so, but Nouvelle Vague is also a far better movie than Breathless, which lurched into iconic status due to its perfect timing and Godard’s preternatural feeling for what educated postwar audiences craved in terms of subject matter and style. There was no screenplay. Truffaut was nominally the screenwriter, but he never got past a thirty-page treatment that fictionalised a story that blazed through the French tabloids in 1952: a low-level gangster stole a car, killed a pursuing motorcycle cop, and then went on the lam with his American journalist-girlfriend. Godard altered the criminal’s name from Michel Portail to Michel Poiccard and talked Belmondo, who was then a near-unknown, into taking the part. Godard changed the American girl’s name to Patricia and had her hawking copies of the New York Herald Tribune along the Champs-Élysées while she sought her own break as a reporter.

Godard also changed Truffaut’s ending, which had Poiccard running hopelessly from his implied but never-shown fate. In Godard’s film, the police catch up with Poiccard and shoot him in the back after Patricia betrays him and divulges his whereabouts. As for dialogue, Godard sometimes wrote it piecemeal in a school notebook while he sat in a cafe before shooting began. More often, he simply had the actors improvise. And if they drew a blank or didn’t get their lines memorised by shooting time, it didn’t matter. Godard shot Breathless handheld using a bulky Caméflex Éclair camera usually used for newsreels, and it was so noisy that all of the dialogue had to be re-dubbed in a studio. He wanted an amateurish look and also the sense of urgency he thought could be achieved with newsreel-stock film, fly-by-night production methods, and forcing his actors to invent many of their lines.

Godard’s professional and personal life is well-documented, especially with respect to the making of Breathless. Linklater’s movie seems to be faithful to the painstaking account in New Yorker film critic Richard Brody’s exhaustively annotated 634-page biography, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As Linklater shows us, Godard embarked on Breathless out of professional envy and anxiety. Nearing thirty and considering himself a prodigy, he was actually the only member of the Cahiers du Cinéma writing cadre—himself, Truffaut, Rivette, Éric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol—not to have directed a feature-length film of his own. Truffaut’s debut feature, Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows, 1959) had won the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival that spring, and it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay in 1960.

Not to be outdone, Godard plundered the Cahiers till so that he could fly himself to Cannes and crash the celebrity parties in search of financing for his own cinematic venture. He hailed from an ultra-wealthy French-Swiss banking family in Geneva, but he disdained actually working for a living except when forced to do so. Theft, especially from the art and rare-books collections of his plutocrat maternal grandfather, was his modus operandi for maintaining his bohemian Paris lifestyle. His father had to save him from prison after one pilfering episode by parking him in a mental hospital for a while. At Cannes, Godard connected with Georges de Beauregard (played by Bruno Dreyfürst in Linklater’s movie), the producer of many new-wave films over the decade. Beauregard raised US$90,000 for Godard’s project, of which US$15,000 was earmarked to pay Seberg, Breathless’s only name star at the time.

Godard’s shooting schedule for Breathless was 23 days, which are compressed to twenty by Linklater for story purposes and organised to follow the sequence of events in Breathless itself. I’m not sure if Godard also shot his film in chronological order, but Linklater’s strategy—which recreates the setups and snippets of scenes—jogs the memories of those who have seen Breathless and allows them to fill in the gaps. This leaves Linklater free to make his own movie, not remake Godard’s.

As Linklater recounts it, Godard’s own strategy was a hostage to Breathless’s severe budget constraints and its director’s ego-driven eccentricities. Every scene was shot in a single take (or occasionally two), which meant he could wrap up a day’s work in an hour or two (on one day, he was done in ten minutes) or even take the day off entirely. This infuriated Beauregard, who was, after all, responsible to his investors for delivering a completed product and didn’t think the director should be wasting his already constricted shooting schedule playing pinball or malingering (as Godard does on day fourteen in Linklater’s fictionalised narrative). This last incidence of creative sloth triggered a threat by Beauregard to cancel the movie altogether and a fistfight between producer and director, whom Godard’s cinematographer Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat in Linklater’s movie) had to pry apart. In his review of Nouvelle Vague for the New Yorker, Richard Brody asserts that Godard’s loafing was actually a manifestation of his insistence on artistic autonomy: “[For Beauregard] time, after all, is money. But, for Jean-Luc, money is time—which is to say, the producer is paying for time that Jean-Luc will use as he sees fit.” Be that as it may, in Linklater’s version of events, Godard’s work ethic improved considerably after the spat with Beauregard.

Godard refused to obtain municipal shooting permits for his locations, so he simply barged into seedy hotels and cafes to grab his interior shots without asking. He also got his Cahiers friends and fans to take minor roles. Truffaut’s then-girlfriend, actress Liliane David (Léa Luce Busato in Linklater’s film), played Poiccard’s former girlfriend whose purse he rifles for walk-around dough (Godard managed to inveigle a quasi-nude scene out of David by having her wriggle out of her lingerie beneath her dress). Rivette played the body of a car-accident victim who reminds Poiccard of his own mortality. The French director Jean-Pierre Melville (Tom Novembre in Linklater) played a pompous intellectual interviewed by Patricia. Godard himself took a bit part that Truffaut had turned down: a passer-by who recognises Poiccard from his newspaper photo and precipitates the inevitable police ambush.

With a cast composed mostly of volunteers, Godard invested much of his budget in a shrewd publicity campaign designed to draw press attention to Breathless even as it was being filmed. He engaged a publicist named Richard Balducci (Pierre-François Garel in Linklater) to embed a freelancer for France-Observateur (Blaise Pettebone in Linklater) with the film crew. His job was to create an aura of anticipation over the film’s future release and to draw attention to the parallels between Godard’s history of pilfering and Poiccard’s fictional larcenies.

Beauregard also hired a stills photographer named Raymond Cauchetier (Franck Cicurel in Linklater’s movie) to take shots on-set for publicity purposes. Cauchetier had begun his career as a news photographer in Saigon during France’s Indochinese war, and with a documentarian’s instinct, he shot rolls of photos of the making of Breathless as well as the publicity stills of the action he’d been employed to take. As a result, he captured Godard’s interactions with his actors and his unorthodox filmmaking style for posterity. The most famous image from Breathless—Poiccard and Patricia strolling down the Champs-Élysées—is not a frame from Coutard’s reels but a Cauchetier photo. The latter’s cache gave Linklater a built-in storyboard, and many of the individual scenes in Nouvelle Vague are clearly tableaux vivants of those shots, including Linklater’s presentation of Godard himself, a theatrical character in his own right, always hovering in the background behind those sunglasses he never took off.

Linklater has some inside-joke fun with Cauchetier’s unique perspective. In his retake of the Champs-Élysées sidewalk scene (day three in his chronology), he has Belmondo and Seberg trailed by a wheeled postal-package cart concealing Coutard, who peers out with his Caméflex from a hole cut into the front. The rolling contraption positioned behind the pair for a rear shot looks hilarious in Linklater’s movie, but Godard actually used something like it so as not to alert police and passers-by that he was filming. Godard instructs the two actors to improvise their dialogue, but because he’s pushing the cart behind them, he can’t hear what they are saying. They look as though their characters are wooing, but Belmondo is actually telling Seberg: “I say whatever is in my head, because we’re being dubbed.” To which Seberg replies: “I have no idea what the fuck I’m doing.”

Although Aubry Dullin is charming in Linklater’s movie, he is no Jean-Paul Belmondo—and it was Belmondo’s presence that made Breathless the movie that it is. A natural athlete who had a brief boxing career in his late teens, Belmondo knew how to float like a butterfly, and in Godard’s film you can’t take your eyes off his restless, muscular body beneath the scarecrow clothes. He is constantly in physical and mental motion, hot-wiring cars, stiffing cafes on the bill, making furtive phone calls to his hoodlum handlers as he frantically tries to scrape together the cash he needs to flee the country, hunting for Patricia and then wriggling between her sheets. Dullin works hard, but he can’t quite muster the bravado, the impulsive energy level, and the quasi-innocent naivety that Belmondo brought to Michel Poiccard and his Humphrey-Bogart-inspired tough-guy fantasies.

Zoey Deutch, on the other hand, is everything vivid that the real-life Jean Seberg as Patricia was not. Godard may have hired Seberg because her blonde, freckled Midwestern looks (she hailed from Marshalltown, Iowa) personified the vacuous Americana with which he had a love-hate relationship. Or perhaps he just wanted a genuine Hollywood star as a publicity draw and knew Seberg’s French husband, François Moreuil (Paolo Luka Noé in Linklater’s movie), who had ambitions of becoming a film director himself. Otto Preminger had cast Seberg as Joan of Arc in Saint Joan (1957) when she was a seventeen-year-old high-school student with limited acting experience. The movie flopped and the critics derided Seberg’s performance but Preminger tried again, giving her the lead role in Bonjour Tristesse the following year, an adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s bestselling teen-coming-of-age novel. That also flopped, and when you watch Breathless, you can see why. Seberg simply lacked the charisma to fill up a movie screen the way Belmondo did, and when the two of them are together in Breathless, even in bed, she’s chemically inert.

Deutch infuses Seberg with all the chemistry the real-life Seberg lacked. When she’s onscreen, she moves effortlessly in and out of Patricia’s character with her pixie hairdo and her conspicuously American-accented French. She works particular magic with Dullin. Stuck in a cramped hotel room on day twelve waiting for Godard to do some directing, she teaches Belmondo how to do the hully gully, the line dance immortalised in the Olympics’ 1959 hit rhythm-and-blues single. It’s an electric moment that they reprise on a cafe floor on day fourteen, and a subtle, Godard-like homage to the enchanting line dance that Anna Karina performs in a cafe with her two co-stars in Godard’s 1964 movie Bande à Part (Band of Outsiders).

Other scene-stealers in Linklater’s film include Dreyfürst as the portly, huffing-and-puffing Beauregard (it’s hard not to empathise with his exasperation). Another, surprisingly, is Penchinat as Coutard. Like Cauchetier, Coutard had been a war photographer in Indochina, and in Linklater’s movie, he’s a calm and steadying force on the set, mediating between Godard’s irritating shooting style and the actors, especially Seberg, who were baffled and dismayed by it. “Good thing the camera loves those two,” he says of Belmondo and Seberg; he’s unperturbed by Godard’s antics, and the show goes on.

Unlike Godard in Breathless itself, Linklater has produced a tightly structured and coherent story out of the material he wanted to work with. Thanks to Truffaut’s outline, Godard did have a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end: a young man not blessed with much upstairs and besotted with ideas of cheap glamour makes a series of mistakes that cost him his life. But Godard couldn’t resist stuffing his story with arch cleverness and his knowledge of cultural artefacts, especially other movies, which is where his knowingness grates most. This may have seemed fresh and exciting in 1960, but it all looks very stale now and the film’s many longeurs make large portions of Breathless excruciating. Linklater understands the value of economy and he reduces an interminable 27-minute hotel-room scene filled with incoherent Satrean ramblings to a brisk ten minutes that include the off-camera hully gully and some flirty exchanges between Seberg and Belmondo. This results in an awkward moment when Moreuil shows up to take Seberg home and finds his wife hanging out with Belmondo clad only in his undershorts.

Besides putting Godard’s perverse working methods on display to comic effect, Linklater expertly explores the interpersonal tensions that simmered but never quite came to a boil during those three weeks, especially with regard to Seberg. Preminger was notorious in Hollywood for his demanding perfectionism and on-set temper explosions—a traumatising experience for a seventeen-year-old girl who hadn’t grown up in show business. The fact that both of the movies Seberg made with him failed didn’t help matters much. She was in Paris in 1959 partly for emotional recovery, and it was Moreuil who talked her into accepting the Breathless role in the first place and then talked her out of quitting as she wearied of Godard’s petty tyranny.

Godard forbade Seberg to wear any makeup for the camera, even though, as Linklater shows, her contract with him specifically called for the provision of a makeup artist. (The real-life Seberg seems to have managed to defy this dictum, as she’s clearly wearing at least lipstick and eyeliner in most of Breathless’s scenes.) Belmondo and the Cahiers crew could handle Godard’s eccentricities and dictatorial ways, but Seberg couldn’t, Linklater suggests. In Nouvelle Vague, we see the first traces of the mental instability that led to her death by apparent suicide at forty. We also see the rickety state of her marriage to Moreuil, which ended in divorce around the time that Breathless was released. Whether Seberg actually had an affair with Belmondo (who was married and the father of two small children at the time) isn’t known.

Linklater does let us down, however, by under-developing Godard’s character. He is good at capturing the insouciance of Godard’s slipshod approach to filming. On day two of the shoot, for example, Godard confounds the script girl Suzon Faye (Pauline Belle) by refusing to let her remove a coffee cup that wasn’t originally in the scene. “Reality is not continuity,” he declares. And Linklater captures Godard’s annoying intellectual pomposity as he issues vatic pronunciamentos designed to show off everything he’s read in his life: “T.S. Eliot said, ‘Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal’” and “Paul Gauguin said, ‘In art one is either a plagiarist or a revolutionary.’” But Linklater slides over Godard’s worse sins of arrogance and petty cruelty (although we do get a hint of the latter in his treatment of Seberg).

Godard had already met Anna Karina by this point, and he wanted her to do a nude scene in the part that Liliane David later took. She was only eighteen, and she had the sense to turn him down. Their four-year marriage, which ended in a 1965 divorce, was a disaster of raging semi-public fights, long unexplained absences by Godard (she had a miscarriage during one of them), and suicide attempts by Karina. A few years later, Godard permanently alienated his lifelong friend Truffaut with a scathing letter denouncing Truffaut’s Academy Award-winning film La Nuit Américaine (Day for Night, 1973) as the work of a “liar.” In other words, Godard was not a nice person, and while Linklater’s film doesn’t whitewash him exactly, it tends to present him as a whimsical, Puck-like mischief-maker in sunglasses.

And yet… superior in many ways though Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague may be, it’s Godard’s Breathless that remains chiseled onto our cultural memory. That’s because Godard really was a genius in his own way. He knew how to make exactly the right decision, at the right time, and in the right place. The single takes miraculously worked. The Champs-Élysées worked as a setting because postwar Paris was the most glamorous and exciting city on Earth. The American touches, including the character of Patricia herself, were just right because postwar Europeans were paradoxically enthralled and repelled by all things American. And Jean-Paul Belmondo happened to be the most brilliant of casting choices for Poiccard.

Godard even picked exactly the right soundtrack for Breathless, commissioning the French jazz pianist Martial Solal to compose a haunting score (not used by Linklater) that epitomised the film’s sense of disillusion and hopelessness. (The responsible party in this was actually Melville, a jazz aficionado; Godard reputedly had little idea initially of what music he wanted.) Godard was unusually lucky, but fortune favours the bold, and Godard was certainly a bold artist. He is credited with pioneering the jump-cut in Breathless, and this technique gives his film a stylish feeling of modern disconnectedness. But, as Linklater’s film shows, it was also just a way of paring down two hours of raw product into the ninety-minute running time that Beauregard demanded.

Breathless made Belmondo an international star. It also saved the professional life of Jean Seberg, who would otherwise now be a half-forgotten Hollywood fame-machine victim. Instead, her New York Herald Tribune T-shirt catapulted her into immortality. A caption at the end of Nouvelle Vague declares: “Breathless is considered one of the most influential films ever made.” Later directors, especially in Hollywood where the filming rules had once been rigid, adopted Godard’s informal and impromptu techniques and generated a new American cinematic vocabulary. And since one of the fruits of postwar Western prosperity was a growing cynicism about the empty materialism it was believed to have fostered, Breathless’s atmospheric moral nihilism resonated. Godard had created a world in which the cops were as ruthless and cowardly as the criminals, and love and betrayal were twins. Patricia’s blank face as she stands over Poiccard’s body on the street in the last frame of Breathless—the only frame that Linklater reproduces in his own film—said it all. Directors like Arthur Penn in Bonnie and Clyde (1968) followed his lead and portrayed thieves and murderers as attractive young rebels against an unforgiving society.

The only problem was Godard himself. He had been the most adventurous and outrageous of all his youthful nouvelle vague cohort. The rest of them—Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer, and others—moved into more conventional kinds of filmmaking. Godard, however, remained stuck at Breathless. He made hundreds of film and video projects over the next 62 years, including 39 full-length features, but they were all slammed-together versions of Breathless, only progressively worse and less able to generate box-office returns. Belmondo made two further films with Godard—Une Femme Est une Femme (A Woman Is a Woman) in 1961 and Pierrot le Fou (Pierrot the Fool) in 1965. Belmondo and Karina looked wonderful in the latter, shot in saturated colour under a Mediterranean sun. But the plot, which concluded with Belmondo’s character shooting Karina’s, painting himself blue, and blowing himself up with dynamite, seemed designed to provoke derision, and it did. Belmondo never worked with Godard again. Some artists have only one great work in them, and only one moment when it all comes together (Hemingway in his early stories, Raymond Chandler in The Big Sleep). Godard was fortunate that his moment came at the right time in history, and that he has had such a talented acolyte in Linklater to chronicle it.

Read the full article here

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using AI-powered analysis and real-time sources.